Grèce, Chine et cetera : point sur notre stratégie d'investissement

After rising sharply in the first quarter of 2015, most equity markets fell back slightly in April. The surge in bond yields, the prospect of a tighter monetary policy in the United States, and uncertainties over the future of Greece as well as economic growth in China all contributed to investors' nervousness and increased their aversion to risk.

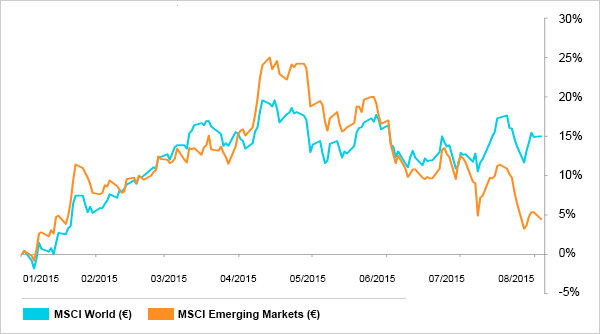

Stock markets year-to-date:

An unchanged environment

But despite greater volatility, there has been little change in the economic and financial environment. In keeping with recent tradition, the International Monetary Fund has just revised its growth forecasts downwards, this time citing the 'unexpected weakness in North America'. This revision only illustrates the structural brakes hanging over growth and point towards growth significantly below the historic average in the coming months. In this context, there is little prospect of a steady rise in interest rates. Meanwhile, low interest rates will continue to render obsolete the principles that have historically guided asset allocation between equities and bonds.

First of these is the principle that considers equities as risk assets and bonds (at least government bonds) as risk-free (or very low risk). In normal times, an environment like the present, dominated by economic uncertainties, weak growth and contained inflation, would suggest an allocation favouring bonds over equities. Today, however, the situation is such that to obtain any sort of decent yield on bonds, you have to make major concessions on debtor quality. But, making this kind of concession in a world dominated by massive debt and weak growth (which reduces the capacity to service this debt) could prove very dangerous. In fact, it amounts to replacing a risk of volatility by a risk of permanent loss (on the bond markets, you are by definition dealing with leveraged companies). Where long-term investing is concerned, volatility is not the best definition of risk.

So, in terms of financial investments, there are no obvious alternatives to equities, provided they are not valued at ridiculous levels. What about current valuations? The fact is that, depending on the ratio that one uses, it is possible to arrive at the conclusion that equities are cheap, expensive or somewhere in between. Firstly, any valuation method based on current interest rate levels shows that equities are undervalued. Secondly, and generalising somewhat, ratios using current or forecast earnings for the next 12 months show that equity valuations are close to their historic average. And thirdly, according to turnover, equity capital, asset replacement value or normalised profits, equities look expensive. The conclusion of all this could be that the return one might expect from equities in future years will be below the historic average but without there necessarily being a major decline.

Equity bias but with realistic expectations

In the current conditions, a strategic asset allocation between equities, bonds and cash is bound to favour of place to equities. This is true even for portfolios whose objective is to generate income rather than capital gains. As Glenn Stevens, Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, said recently, the big question is how can an adequate flow of income be generated for the retired community in the future in a world in which long-term nominal returns on low-risk assets are so low? The answer is that there is no miracle solution and you have to be prepared to take more risks to achieve the desired return.

However, this should not be interpreted as an endorsement of passive management. The fact is that, given the historically low level of bond yields, there is little point in making major adjustments between asset classes (increasing/reducing equities to the detriment/in favour of bonds) unless one were to bet on short-term movements in these asset classes. This type of market timing is always a hazardous exercise, even though it seems to be the main concern of many fund managers (or their clients). The market fluctuations over recent weeks as the Greek situation unfolded are a good illustration of the futility of this approach. Despite daily movements up and down of varying degrees, the market has remained virtually unchanged overall. Changes in the allocation between equities and bonds based on more tangible elements, such as the relative valuation of the two asset classes, are harder to assess while bond yields are so low, unless a particularly excessive valuation or very unfavourable earnings prospects were to suggest a negative return on equities. But that isn't the case yet.

Active management combining quality and dividends

Active management within asset classes, especially equities, is therefore all the more vital. While the economic and financial environment remains weak, it is particularly important not to make concessions in terms of the quality of the companies in which one invests. Since no fund manager would admit to buying poor quality companies, we will just focus here on reiterating what makes for a good quality company. We define it as a company with a sustainable competitive advantage which gives it an edge over the competition and allows it to create entry barriers to its markets. This gives companies better control over their destiny and enables them to capitalise on their strengths, thereby creating a virtuous circle. Such companies are characterised by a high return on equity, little debt and low capital intensity. Note too that in the current context, there is a particularly wide gap between their return on equity and cost of financing, theoretically justifying much higher valuation multiples.

A second investment theme, closely linked to quality, is that of dividends. One of the investment strategies that has produced the best results over the long term consists of buying companies combining a high dividend yield and a low payout ratio. The high dividend yield makes these companies particularly attractive for investors seeking regular income, while the low payout ratio is reassuring with regard to the sustainable nature of the dividend, and even its potential to increase.

Contrarian investing

Another aspect related to active management consists of exploiting share price fluctuations to sell/reduce a position if the valuation is excessive and to buy/increase a position when the valuation is attractive. To obtain above-average returns, an investor needs to be prepared to act anticyclically. One way of doing this is to look for companies whose share price has fallen substantially, to analyse the reasons for the fall, and form your own opinion on the validity of these reasons and whether they are likely to persist. For example, the recent rout on the Chinese market dragged down with it a number of good quality Asian companies whose current share price offers an attractive opportunity for a long-term investor.

We have used the latter approach to deal with the stock market fluctuations prompted by events in Greece and China. Apart from good quality stocks in Asia, opportunities also arose in the energy and technology sectors. We have therefore taken profits on a number of positions whose share price had risen appreciably and invested the proceeds in these currently out-of-favor sectors. In this way, we reduced the risk profile of our funds without fundamentally adjusting their asset allocation.

It goes without saying that contrarian investing by definition requires a long-term investment horizon. It involves buying companies whose valuation is attractive because a majority of investors do not like them at a certain point in time. It would be naïve to think that these investors change their mind as soon as we bought. On the contrary, the stock price of these companies will often continue to decline for a while, negatively affecting our performance but giving us the opportunity to increase our position. The fate of a contrarian investor is to be too early (in buying as well as in selling). Buying low usually does not feel good, but that is the sacrifice required to achieve above-average returns. To quote Howard Marks, Chairman of Oaktree Capital Management: "It feels much better to buy assets while they are rising. But it is usually smarter to buy after they have fallen for a while." Good things take time.