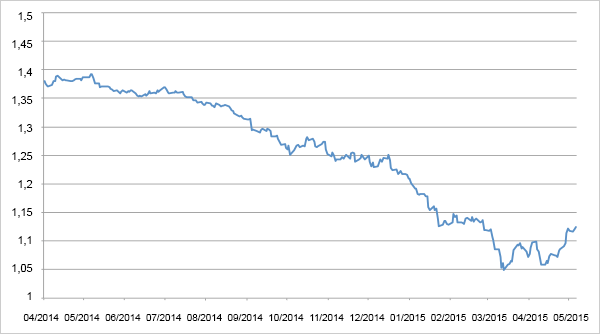

Strong Dollar or weak Euro?

Within the space of a year, the US dollar has risen against the euro from around 1.38 USD/EUR to 1.12 USD/EUR. That is an increase of over 20%. The currency effect alone therefore made investments in USD an attractive prospect for euro investors. However, this positive currency effect is not just limited to investments in the dollar. The euro was weak against most currencies.

Within the space of a year, the US dollar has risen against the euro from around 1.38 USD/EUR to 1.12 USD/EUR:

That is an increase of over 20%. The currency effect alone therefore made investments in USD an attractive prospect for euro investors. However, this positive currency effect is not just limited to investments in the dollar. The euro was weak against most currencies.

| Appreciation against the euro since 01/04/2014 | |

| US dollar | +23% |

| Taiwan dollar | +23% |

| South Korean won | +22% |

| Swiss franc | +22% |

| Singapore dollar | +17% |

| South African rand | +16% |

| Canadian dollar | +14% |

| British pound | +13% |

| New Zealand dollar | +11% |

| Australian dollar | +9% |

| Mexican peso | +7% |

| Japanese yen | +6% |

| Brazilian real | +3% |

| Norwegian krone | -1% |

Source: Bloomberg

In the past few months, currency allocation has therefore been of vital importance to successful investment management. As the EUR/USD exchange rate always remained between 1.20 and 1.50 USD/EUR in the years beforehand, both the speed and scale of the US dollar's appreciation proved to be surprising.

Aside from investors, the currency development also obviously affects the eurozone's foreign trade and therefore the real economy. Intuitively, one would expect exports to have benefitted from the weak euro in the past few months. Indeed, the foreign trade balance surplus increased by over EUR 42 billion to EUR 194.8 billion in 2014, meaning it experienced growth of more than 27%. But what is surprising is that exports "only" increased by 2%, while imports remained practically unchanged. And if one also considers that the surplus only accounts for 2% of the eurozone's entire gross domestic product, then the 27% growth rate constitutes a positive contribution of approximately 0.5% to the eurozone's economic growth.

The mood among export-oriented companies in the eurozone is also good thanks to the weak euro (and therefore better than a year ago); and yet, despite a 20% depreciation against the leadingtrade currency, the mood is not euphoric. Why was the effect not greater? The following arguments are always recounted in connection with this question:

- the yen, a major player on the world market, has also depreciated significantly against the US dollar;

- as a result of globalisation across the entire value chain, the eurozone's contribution has shrunk considerably over the course of the past few decades;

- export-oriented companies have long since hedged a large proportion of their turnover in foreign currencies;

- and many increasingly well-informed clients are aware of the currency effect and are demanding the resulting cost advantage as discount.

The export advantages are countered by the costs of the depreciation of a currency. Apart from a possible general loss of confidence, the costs of depreciation also bring about imported inflation. In view of the global concerns and fears regarding deflation, however, this risk currently seems to be largely theoretical. But it does in fact exist. For instance, if energy prices in USD had remained unchanged in the past year, the depreciation of 20% would have led to inflation of 2% in the case of energy prices making up approximately 10% of the inflation basket and the prices of other components also remaining unchanged. However, as the oil price in USD fell by 45% almost in parallel to the depreciation of the euro, it did not bring about this inflation effect. In terms of inflation,the depreciation therefore did not have any consequences. However, domestic consumer spending did not benefit from the fall in oil prices, like in the USA.

One might therefore debate whether from an economic point of view, the advantages of a structurally weak currency offset the risks in the long term. With regard to the specific case of the euro over the past few months, the key question is whether the weak annual performance - which did not have any effects on inflation - marked the beginning of a structurally weak euro.

Then it would certainly be of interest to investors in the long term. Were the past few months just a series of positive or negative spells depending on individual positioning, or do we now need to make a fundamental adjustment?

Even though the weakness of the euro was to a certain extent surprising and it depreciated against practically all currencies at the same time, that itself is no reason to label the common currency as structurally weak in comparison to other global currencies. Indeed, a currency rising or falling by 25% against another currency is not unusual. For example, if one looks at the development of the euro since 1999, such occurrences seem to be more the norm than the exception.

But even before the birth of the euro, there were examples of sharp movements. For instance, the strongest historic increase in the US dollar against the German mark (DM) took place within the space of a year between the summers of 1980 and 1981. Back then, the dollar rose by almost 50% and yet the DM still retained its status as a structurally strong currency.

Such high levels of volatility on the currency markets indicate that the search for a "fair" exchange rate value is very difficult. It is of course complete rubbish to assume that a large economy like that of the USA or the eurozone has increased or decreased in "value" against another by a quarter within the space of a few months, just because the exchange rate has risen or fallen by 25%.

However, purchasing power parity and offsetting the balances of payments remain as very long-term concepts for a fair exchange rate. The fundamental idea behind both concepts is that theadjustment of the economic imbalances between different currency areas is most easily (and most rapidly) achieved via exchange rates.

However, by taking Switzerland as an example, one can easily recognise the limits of these concepts. Switzerland is surrounded by euro countries and so logically, the vast majority of its foreign trade is done with these countries. Since the euro came into force, Switzerland has had an average trade deficit with the eurozone of around CHF 25 billion per year. With total imports amounting to CHF 186 billion in 2013, the Swiss franc should have depreciated against the euro over the course of time. Equally, on the basis of different purchasing power models, it was always overvalued between 20 and 40%. Despite this, the Swiss franc has increased from approximately 1.60 CHF/EUR to around 1.04 CHF/EUR since the euro was introduced in 1999.

It is therefore only logical that these elements are rarely addressed in financial sector analyses. They devote much more attention to political stability and the political significance of an economic area, relative economic growth, inflation and above all the interest rate and monetary policy of central banks.

For instance, the dollar's strength in the past few months is explained by the fact that the monetary policy of the Fed became more restrictive (end of the Fed's bond purchases and first discussions about interest rate hikes), while the European and Japanese central banks became increasingly expansive in the same time period (bond purchasing programmes in ever larger volumes).

However, the prognoses do not focus on the current situation but on how the statistics or the expectations and perceptions of the market participants will develop. For example, the current expectation is that the geopolitical importance of Switzerland will hardly change in the coming months. But in the event that further geopolitical crises occur, the Swiss franc's status as a "safe haven" will see it increase in value even further. Another expectation is that while monetary policy in the USA continues to be very expansive, it will tend to be rather more restrictive than in Japan or the eurozone. This would support the view that the dollar is set to increase further. Of course, this approach only allows for the recognition of trends. Logically, it does not result in establishing an exact price target for one or several currencies. If there are many expectations in favour of a currency, then it should increase in the coming months; if there are many against it, it should decrease.

If I only consider the most important currency areas, then my current expectations lead me to compile the following table.

| USD | EUR | CHF | GBP | JPY | |

| Monetary policy | + | - | - | + | - |

| Deflation/Inflation | ? | ? | + | ? | ? |

| Growth | + | - | - | +/- | - |

| Social and political stability | + | - | + | +/- | + |

| Geopolitics | + | ? | + | ? | ? |

| Purchasing power parity (OECD) | - | + | - | - | + |

| Foreign trade | -- | + | - | - | + |

| Total | 4:3 | 2:3 | 3:4 | 1:2 | 3:2 |

Source: Bloomberg/BLI

The individual estimations can certainly be discussed and I would like to invite each of you to compile your own table and add the currencies that you would like to consider. For certain currencies, however, other aspects which are not listed in the table must be taken into account. For instance, with regard to the Canadian and the Australian dollar, the expected development of raw materials prices should be included in view of the significance of the raw materials sector for these countries.

It is not currently possible to identify any clear trends for or against a currency from the above table. Taking an aggressive position towards a currency therefore makes no sense. This means that one should invest broadly. Our BL Global Flexible EUR fund, which is oriented towards eurozone investors and is not subject to any currency restrictions, is currently structured in such a way. Its current currency breakdown is 46% in EUR, 15% in USD, 11.5% in CHF, 6.5% CAD, 3% in JPY, 5% in GBP and 13% in other currencies.